On the morning of 25th July 1865, a secret was unveiled at Cavendish Square, London that would scandalise Victorian Society – the claim that the respected but enigmatic Dr James Miranda Barry, Inspector General of Military Hospitals was in fact a woman.

Dr James Barry was one of the most distinguished doctors of his day, having served as surgeon in various regiments including South Africa, Jamaica and Malta.

How then was it possible to have hidden his gender for so long?

Dr James Barry’s early career

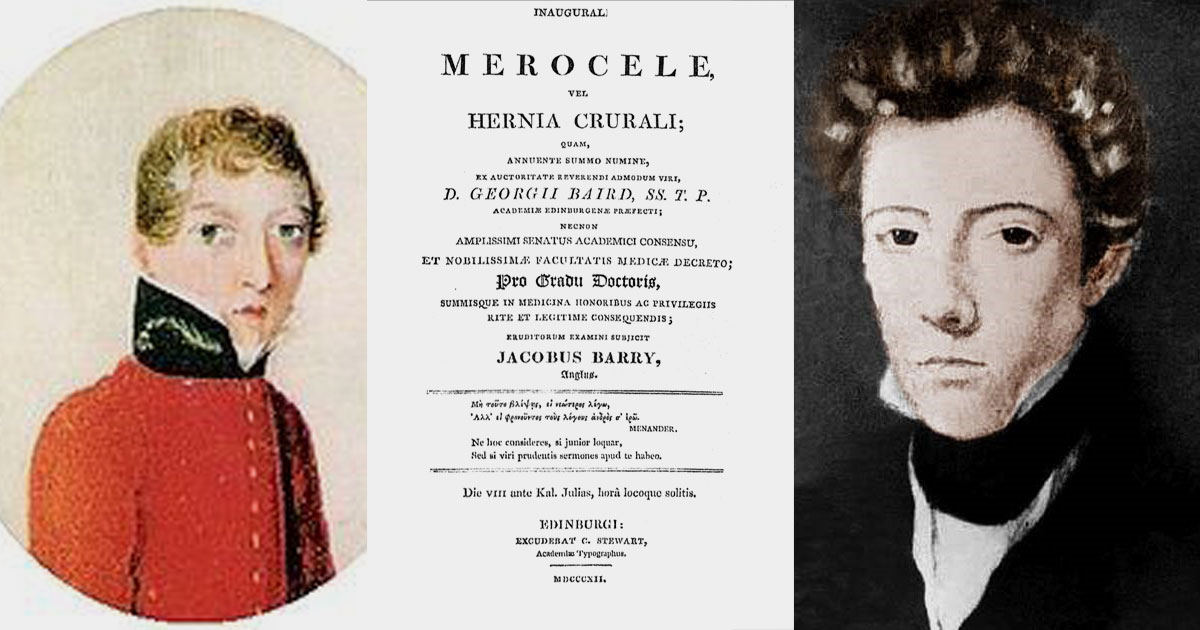

The first records of James Miranda Barry are those of a prodigious student. Barry qualified with a Medical Doctorate in 1812 from the University of Edinburgh, presenting his thesis in Latin “De Merocele” on hernia of the groin.

He went on to become an apprentice to one of the finest teachers of the profession, Sir Astley Cooper at St Thomas’ Hospital.

In 1813 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, Barry attended a course in Military Surgery during took the examination for the Royal College of Surgeons of England, and joined the British Army.

Dr James Barry’s death and infamy

By 1864 after a career for 46 years in the British Army as an officer and a gentleman, a physician and surgeon, Barry had risen to the rank of Inspector General, second only to the Director General of the Army.

He returned to England that year unwell. At the time London was in the grip of an outbreak of dysentry that left 3000 dead in Marylebone alone in the first week. Barry too succumbed and died on July 25, 1865.

Barry left strict instructions that on death his unexamined body should be left in a nightshirt and wrapped in a winding sheet.

And there the story would have ended, had it not been for the not been for the testimony of Barry’s charwoman, Sophia Bishop, who unleashed an immense scandal on Victorian society with her allegations that Barry was in fact a woman.

Was James Barry a woman?

Dr James Miranda Barry was allegedly born into humble beginings although there is no documented evidence of his existence prior to the matriculation roll of 1809. It is widely held that he was born as Margaret Ann Bulkley, the daughter of a greengrocer from Cork.

Barry appears to have had ‘protectors’ throughout his career, who may or may not have realized his secret, but certainly kept it hidden. These included General Miranda (then running a full blown revoultionary campaign in South America) and Lord Buchan, Barry’s university sponsor.

But how would Barry have passed a medical examination on joining the Army? At that time doctors with a degree and the experience that Barry brought from working with Sir Astley Cooper were badly needed and it may we be that Barry was exempt a medical. Equally at that time, many medicals were cursory, involving little more than unbuttoning a single waistcoat button.

Personal privacy was one of the priveleges of rank and Barry conducted himself as a consummate, if effeminate, gentleman – he was always immaculately dressed, wore high heeled boots, was a splendid marksman, accomplished coach-driver and is said to have flirted with the ladies. Barry was even involved in a duel, fought with pistols – fortunately without harm to either party.

But throughout his career Barry was never far from scandal. He was a belligerent character and is reported to have publicly berated Florence Nightingale whilst serving in the Crimea.

Slanderous statements linked Barry romantically and homosexually to his patron Lord Sommerset, Governor of South Africa. Eventually this gossip reached such a level that Sommerset was recalled and Barry faced charges (of which he was subsequently cleared) of unprofessional conduct, was dismissed from office and posted to Jamaica. This legacy of doubt, about Barry’s sexuality, rather than his gender, persisted throughout his life.

After his death, calls for an enquiry and for his body to be exhumed became the subject of prolonged bureacratic debate within the Army office, however as they were keen to quash the scandal, no action was taken and his file was closed.

James Barry’s legacy

Barry was an ardent reformer throughout his career.

In South Africa Barry introduced a systematic plan for smallpox vaccination in the Colony, some 20 years before such a measure was introduced in England. Long before scientists understood why wounds turned septic or how disease spread, Barry was a devout advocate of rigorous cleanliness, insisting on daily linen changes, frequent dressing changes and fresh air. He campaigned against overcrowding, bad drainage and lack of ventilation in the prisons and the hospitals of Cape Town, practicing preventive medicine well ahead of its time.

In Cape Town he was said to have performed the first Caesarian section in the English-speaking world. The survival of both mother and baby brought him widespread acclaim.

He became unpopular for insisting that district surgeons must attend prisoners, convicts and paupers free of charge, with the account going to the local authority. He rationalized fees for the profession, insisted that apothecaries must be licensed and disallowed dispensing arsenic and opium without a prescription, bringing him into conflict with medical colleagues.

When Barry was transferred to Jamaica in 1831, he arrived at a country which had the worst health record in the Empire and considerable mortality from Yellow Fever. Hygiene was primitive and rum was in abundance. Once again Barry campaigned for better conditions for the soldiers, whose barracks were built in low marshy conditions with no balconies.

Later transferred to St Helena, Barry undertook an enormous workload as Principal Medical Officer, and again, showed that he was outstandingly modern. He persuaded the Governor to allow him to employ a respectable woman as the matron, ensured a chaplain was appointed and enabled a wing of the regimental hospital to be equipped as a separate civilian hospital.

Throughout his career Barry continued his work with passion and zeal. He was an obsessive letter writer and managed to push through many reforms improving conditions for wounded soldiers and native inhabitants in colonial outposts.

Despite the circumstances of his gender, his tireless advocacy for wounded soldiers is the legacy for which he should be remembered. He was an outstanding surgeon and practiced preventive medicine years ahead of his time.

Barry is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. The grave and headstone are overgrown and derelict but the inscription reads:

DR JAMES BARRY

INSPECTOR GENERAL OF ARMY HOSPITALS

DIED 15TH JULY 1865

AGED 71 YEARS

Barry in fact died on the 25th of July.

Just as his death inaccurately recorded, Barry’s extraordinary achievements remain overshadowed by the controversy of his gender.

But if he was indeed born a woman then his death in 1865 is all the more remarkable – being the year that Elizabeth Garrett Anderson graduated as the first woman doctor in Britain.